The trek from Tsurpu to Yangpachen is probably one of the most popular treks in the Lhasa area of Tibet. We went in the off-season, which is our privilege as the local foreigners-in-residence. Our official title, given by the part-owner of TU student's favorite bar and written on our bills is: "local foreigners". Apparently we are considered a slightly different animal, even in the eyes of seasoned Tibetan tour guides. These are the kinds of people that frequent our favorite bar, the Tibetan musicians and the tour-guides. In the off-season, some of the same tour guides can be found in the back room every single night. It is this particular breed of modern Tibetan, often educated in Nepal and/or India, and current with all the best Chinese trends and American music, that is capable of dubbing TU students "local foreigners". Why, in this post-post-modern world of globalization is this no longer a contradiction in terms? Or even more to the point, why was it this term that came so easily, almost as an afterthought? The normal chee-gyay looks very much like us, but can only stay a month or three at most-usually less-and rarely knows any Tibetan. The foreign TU student is in Lhasa for wildly differing reasons, but what is truly distinctive is that both TU students and Tibetan tour guides versed in the globalized world are liable to be found with the same kind of look on their face. It is one that reveals a kind of reflexive knowing about the truly absurd post-modern situation they find themselves in, one which, regardless of their recognition of it, gives them no respite from the queerness of it all. Perhaps it is because both peoples are distinctly aware of their own attempt to take advantage of the very absurdity they find so disturbing. Tour guides take advantage of foreigners not only as their patrons and cash-cows (or cash-yaks as the case may be), but also intellectually, as open faucets to the world of the modern flow of information. Often hoping to find a connection to learn more languages, more modern American phrases, more hip hop references, more ways to feel cool, to make money, or to make some kind of sense of it all (far more rare), these tour guides are anything but naive. Foreign students want the same kinds of things-they want to suck the language out of the people they meet, they are hungry for ideas, mannerisms, colloquialisms, anything that will help them feel like they're the slick foreigner who can navigate Lhasa with ease. Anything that will lead them to their PhD thesis, to ideas for research, to contacts they can interview. But in the end they find themselves in the same bar, playing and listening to the same music, wondering if they can forget what might happen tomorrow. What makes these two communities see the same look in each other's eyes is the knowledge that their worlds are connected in ways that they don't quite understand, but that are both enticing and dangerous.

A person, if they could think of it, might ask what it means to have the feeling of globalization. An acquaintance of mine went from growing up in a farming-yaking herding culture to being a computer programmer trained in India and then a tour guide company owner who communicates in four languages on a daily basis and meets people from all over the world, both online, and in person in the ancient capital of Tibet. While this might sound fascinating or amazing, what is odd about the feeling of globalization is that, it's not. What one considers abnormal becomes normal, or more likely we simply lose the idea of normality all together and the feeling is one of floating about without a rudder--or any of the other over-used metaphors for this feeling. It can't quite be described because that's exactly what it is--the weirdness of not really being able to identify what one feels about it, or even what exactly this 'it' is. Many Tibetan and Chinese people are still not very familiar with this feeling, but the multi-lingual, multi-talented tour guides of Lhasa and the college educated globe-trotting twenty somethings of Tibet U. are familiar with it, and it is this felt sense they find in common. How this all relates to trekking I'm not quite sure.

The trek five of us decided on is one I was particularly excited for as we would be hiking through the highest permanent settlement in the world and leaving from one of my favorite places near Lhasa, the Karmapa's home of Tsurpu Monastery.

Here sits Tsurpu Monastery at sunset or sunrise-it looks identical at both these times. We will trek towards that mountain in the background, skirt around it, and head up to the village of Leten, the highest permanent settlement in the world.

Here sits Tsurpu Monastery at sunset or sunrise-it looks identical at both these times. We will trek towards that mountain in the background, skirt around it, and head up to the village of Leten, the highest permanent settlement in the world. The sun over the chorten karpo (white stupa) at Tsurpu Monastery.

The sun over the chorten karpo (white stupa) at Tsurpu Monastery. It is quite cold in the early morning as we leave with the sun rising at our backs. We had to go and get our guide who decided to sleep in a little, probably assuming that as foreigners we really didn't know what we meant by saying we wanted to leave by 7am. His trusty steed, Tondrup, begrudgingly carried all five of our packs, the true hero of the outing. Tondrup was a little hard to handle at first, and moved slower than a yak, but by midday he was moving far faster than the rest of us--perhaps it was a rough night of partying. It was, after all, quite a celebration the night before our departure:

It is quite cold in the early morning as we leave with the sun rising at our backs. We had to go and get our guide who decided to sleep in a little, probably assuming that as foreigners we really didn't know what we meant by saying we wanted to leave by 7am. His trusty steed, Tondrup, begrudgingly carried all five of our packs, the true hero of the outing. Tondrup was a little hard to handle at first, and moved slower than a yak, but by midday he was moving far faster than the rest of us--perhaps it was a rough night of partying. It was, after all, quite a celebration the night before our departure: Although it is difficult to get any kind of picture in this small one-room eatery, there were up to fifteen people dancing about the yak-dung stove listening to VCDs blaring out of the one TV in the corner. This apparently went on till very late, as it was quite a ruckus when Martin and I returned past 11pm to see if they sold toothbrushes (which they did).

Although it is difficult to get any kind of picture in this small one-room eatery, there were up to fifteen people dancing about the yak-dung stove listening to VCDs blaring out of the one TV in the corner. This apparently went on till very late, as it was quite a ruckus when Martin and I returned past 11pm to see if they sold toothbrushes (which they did). Our guide and his mother in their small home just outside the monastery walls. They also seemed to have another home up in the small settlement of Leten.

Our guide and his mother in their small home just outside the monastery walls. They also seemed to have another home up in the small settlement of Leten. Here we are, the sun still not yet reaching us up this high in the valley. The difference in temperature when we reached the sun up ahead in the above picture was easily ten degrees, or at least it felt like it. In the picture above you can see Gregor in blue and Alice's sister in red, following closely behind Martin (who had got a little water on him coming over the creek and was just now realizing that his pants were freezing solid) and Alice (who's bad circulation was causing her hands to turn blue inside her gloves).

Here we are, the sun still not yet reaching us up this high in the valley. The difference in temperature when we reached the sun up ahead in the above picture was easily ten degrees, or at least it felt like it. In the picture above you can see Gregor in blue and Alice's sister in red, following closely behind Martin (who had got a little water on him coming over the creek and was just now realizing that his pants were freezing solid) and Alice (who's bad circulation was causing her hands to turn blue inside her gloves). No one fell into this creek, but there was a lot of ice, which caused delight in some of us, and fear in others. I'm not sure how long it took them to cross over to where I was, but I found this while I waited:

No one fell into this creek, but there was a lot of ice, which caused delight in some of us, and fear in others. I'm not sure how long it took them to cross over to where I was, but I found this while I waited: Om mani padme hum

Om mani padme hum See the moon?

See the moon? We planned our first day to be the longest and stopped at Leten for only an hour or so before moving over the pass. This is one of the few houses that make up Leten, and one of the many dogs...

We planned our first day to be the longest and stopped at Leten for only an hour or so before moving over the pass. This is one of the few houses that make up Leten, and one of the many dogs... This picture looks back at Leten as we leave sometime in the afternoon (I think).

This picture looks back at Leten as we leave sometime in the afternoon (I think). Here we are coming up towards a lower pass, an hour or two (?) below Lasar La. It is a bit hard to remember exact times for me, the altitude definitely effected our whole party and I recall beginning to feel slower and slower in both body and mind. However, we passed over Lasar La without much ado and as soon as we began our decent, I began to feel better.

Here we are coming up towards a lower pass, an hour or two (?) below Lasar La. It is a bit hard to remember exact times for me, the altitude definitely effected our whole party and I recall beginning to feel slower and slower in both body and mind. However, we passed over Lasar La without much ado and as soon as we began our decent, I began to feel better. See Thondrup and our guide way ahead of us? That's how far they were for most of the journey, at times they would go up over a mountainside and out of sight, but soon enough we would all come plodding along after them and see their distant silhouette. The trail was actually quite obvious almost the entire way, however, there are two turns you really need your guide to show you. Next time I would go without a guide, but a horse or a Yak makes the whole experience much more enjoyable.

See Thondrup and our guide way ahead of us? That's how far they were for most of the journey, at times they would go up over a mountainside and out of sight, but soon enough we would all come plodding along after them and see their distant silhouette. The trail was actually quite obvious almost the entire way, however, there are two turns you really need your guide to show you. Next time I would go without a guide, but a horse or a Yak makes the whole experience much more enjoyable. This dog from Tsurpu Monastery followed us for two days--almost all the way to Yangpachen-- and returned with our guide.

This dog from Tsurpu Monastery followed us for two days--almost all the way to Yangpachen-- and returned with our guide.

Notice how there is more water flowing and less ice? We've crossed the pass called Lasar La and are on our way down to a nomad settlement! I even take off one of my jackets here as the temperature has risen again and the sun is strong even at this time in the afternoon. We don't stay in the little "town" recommended by the Lonely Planet Guide because our guide says he doesn't trust the people there. He wants to travel farther before dark and take us to a place where his extended family lives. Instead we negotiate a closer nomad settlement where he knows people, although he still seems uncomfortable for some reason.

Notice how there is more water flowing and less ice? We've crossed the pass called Lasar La and are on our way down to a nomad settlement! I even take off one of my jackets here as the temperature has risen again and the sun is strong even at this time in the afternoon. We don't stay in the little "town" recommended by the Lonely Planet Guide because our guide says he doesn't trust the people there. He wants to travel farther before dark and take us to a place where his extended family lives. Instead we negotiate a closer nomad settlement where he knows people, although he still seems uncomfortable for some reason. This picture was taken from the roof of the small building we stayed in. The sun is setting and the herders are bringing the sheep and yaks back home. The family had three little ones and seemed friendly enough. They mostly avoided us and kept to themselves, putting us outside of their home in the small building that seemed to serve as a shrine area:

This picture was taken from the roof of the small building we stayed in. The sun is setting and the herders are bringing the sheep and yaks back home. The family had three little ones and seemed friendly enough. They mostly avoided us and kept to themselves, putting us outside of their home in the small building that seemed to serve as a shrine area: You can see all the tankas on the walls, the large shrine was along the right wall, out of sight in this picture. It was freezing in this room without a stove and although most people slept alright, I had a horrible night shivering most of the time and feeling like I was going to vomit. I ended up inside my sleeping bag with all my clothes on, plus martin's green jacket, my hat and gloves, and I still wasn't warm. For whatever reason, sometime around 7am the next morning, I was fine. Altitude does funny things.

You can see all the tankas on the walls, the large shrine was along the right wall, out of sight in this picture. It was freezing in this room without a stove and although most people slept alright, I had a horrible night shivering most of the time and feeling like I was going to vomit. I ended up inside my sleeping bag with all my clothes on, plus martin's green jacket, my hat and gloves, and I still wasn't warm. For whatever reason, sometime around 7am the next morning, I was fine. Altitude does funny things. Good Morning! Time to get trekking.

Good Morning! Time to get trekking. The shadows of sunrise still clinging to the valley floor.

The shadows of sunrise still clinging to the valley floor. as we start out again with our trusty steed...Thondrup! He was actually a hard sell for the Travers girls who really wanted yaks. It took many persuasive discussions to convince them that a horse was better and faster and even then it was only that the yaks were far up the mountain side when we reached Leten that convinced Alice we weren't going to get yaks to hang with us on our trip. I think our guide just liked the old horse better than his yaks.

as we start out again with our trusty steed...Thondrup! He was actually a hard sell for the Travers girls who really wanted yaks. It took many persuasive discussions to convince them that a horse was better and faster and even then it was only that the yaks were far up the mountain side when we reached Leten that convinced Alice we weren't going to get yaks to hang with us on our trip. I think our guide just liked the old horse better than his yaks. It takes a couple of ropes and a bunch of brute strength to get all our packs up onto Thondrup.

It takes a couple of ropes and a bunch of brute strength to get all our packs up onto Thondrup. It was unimaginably cold at this point, but perhaps I was still feeling the effects of altitude sickness.

It was unimaginably cold at this point, but perhaps I was still feeling the effects of altitude sickness. Here we are on the morning of day 3 of our expedition (day two of actual trekking). This day was far easier and full of amazing views and perfect weather.

Here we are on the morning of day 3 of our expedition (day two of actual trekking). This day was far easier and full of amazing views and perfect weather. A small settlement along the way to the Ani Gompa before Yangpachen.

A small settlement along the way to the Ani Gompa before Yangpachen. Our guide had seemed in a hurry on the first day, but today he waited ahead for us and spent most of the time close enough to yell at.

Our guide had seemed in a hurry on the first day, but today he waited ahead for us and spent most of the time close enough to yell at. Here you can get a small sense of the beauty we encountered. The sky was a perfect blue the whole day, and we were able to see the distant snowcapped ranges for much of it.

Here you can get a small sense of the beauty we encountered. The sky was a perfect blue the whole day, and we were able to see the distant snowcapped ranges for much of it. The crew on the final stretch of the trek before the Ani Gompa.

The crew on the final stretch of the trek before the Ani Gompa. Here we are finally approaching the Ani Gompa, what a sight!

Here we are finally approaching the Ani Gompa, what a sight! We arrived just as the nuns were coming out of the temple for a short prayer break. They are all hurrying into the grass to pee before filing back into the chanting hall.

We arrived just as the nuns were coming out of the temple for a short prayer break. They are all hurrying into the grass to pee before filing back into the chanting hall.This is where our guide, the dog, and Thondrup left us. We had a wonderful lunch of cheese and bread and chocolate and our guide slowed enough so that I could understand him. We were able to talk a little and I found out he needed sunglasses and new shoes and a book in Tibetan for learning English. Unfortunately I didn't return to Tsurpu before leaving Tibet for winter break, but I plan to bring what I can to him when I return.

The main hall was, as the rest of the Ani Gompa, was nestled up next to sheer cliffs with boulders that jutted out at odd angles and created the sense of a giant tortoise that stood guard over the nunnery.

The main hall was, as the rest of the Ani Gompa, was nestled up next to sheer cliffs with boulders that jutted out at odd angles and created the sense of a giant tortoise that stood guard over the nunnery.Leaving this place was quite an odd experience, but we were all keen to move on and stay in Yangpachen, and it seemed easy enough at first. Of course, we had to deal with some sort of Tibeto-Chinese mafia character who was the only person who could collect money from foreigners in the area. Why? Apparently because he said so, or his mom did, or something to that effect. After approaching several house holds and being continually referred back to the overpriced young man we decided there were no other options but his tractor and took a long ride filled with black smoke and a snuff sniffing grandfather.

Here's a picture of the only vehicle in the area. It is a two-wheeled tractor motor attached to a two-wheeled steel cart. I question the utility of such a vehicle, but Martin informs me that they are apparently all the rage even up in Mongolia and Russian Buryatia. What they do well is produce absurd amounts of black smoke and horrible sounds. But they also cover distances at the speed of a tortoise and can get through most rivers that cross the roads without much worry.

Here's a picture of the only vehicle in the area. It is a two-wheeled tractor motor attached to a two-wheeled steel cart. I question the utility of such a vehicle, but Martin informs me that they are apparently all the rage even up in Mongolia and Russian Buryatia. What they do well is produce absurd amounts of black smoke and horrible sounds. But they also cover distances at the speed of a tortoise and can get through most rivers that cross the roads without much worry.

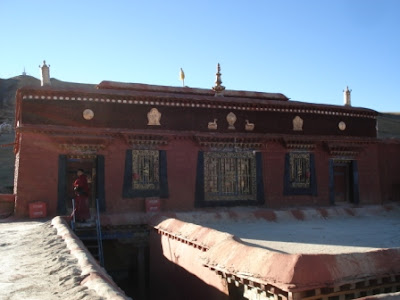

Our view on the ride was quite pretty, when the smog from the engine wasn't in our eyes. They "drove" us all the way over to Yangpachen where we were able to stay the night in the monastery. The monks whipped out fancy cell phones and checked with their superiors, checked our passports and student visas, and kept one to make sure it was all cool with the police. Then we got the tour from one of the Khenpos. Much of the monastery had been rebuilt very recently and parts were still being built. The shedra looked like the paint was still drying.

Our view on the ride was quite pretty, when the smog from the engine wasn't in our eyes. They "drove" us all the way over to Yangpachen where we were able to stay the night in the monastery. The monks whipped out fancy cell phones and checked with their superiors, checked our passports and student visas, and kept one to make sure it was all cool with the police. Then we got the tour from one of the Khenpos. Much of the monastery had been rebuilt very recently and parts were still being built. The shedra looked like the paint was still drying. We stayed in the government official's sitting room at the Sharmapa's seat of Yangpachen Monastery. Here's the roof above where we stayed. In the room in front of that monk above the ladder there is an amazing shrine room full of pictures of the "other" Karmapa and many thankas of the Sharmapas, along with a small silver and gold stupa with the remains of one of the Sharmapas in it. It wasn't until Alice asked, "who's that?" pointing to a picture next to Sharmapa, that we found out where we were.

We stayed in the government official's sitting room at the Sharmapa's seat of Yangpachen Monastery. Here's the roof above where we stayed. In the room in front of that monk above the ladder there is an amazing shrine room full of pictures of the "other" Karmapa and many thankas of the Sharmapas, along with a small silver and gold stupa with the remains of one of the Sharmapas in it. It wasn't until Alice asked, "who's that?" pointing to a picture next to Sharmapa, that we found out where we were.Early the next morning we walked from the monastery over to the hot springs, which are somewhat outside of the town of Yangpachen. It took us quite a while to reach our goal, but we enjoyed our time talking of books and ideas, name histories, dreams and acting.

Ahhhhh, relaxing in the Yangpachen hot springs. There were Chinese men in full pin-striped suits and shiny leather shoes chillin by the pool playing cards. At this point we were so hungry and tired we ate a pound of crackers each and all got coca~cola from the locals.

Ahhhhh, relaxing in the Yangpachen hot springs. There were Chinese men in full pin-striped suits and shiny leather shoes chillin by the pool playing cards. At this point we were so hungry and tired we ate a pound of crackers each and all got coca~cola from the locals.We barely caught a ride in the back of a small white truck, which dropped us off in another town where we tried to hitch a ride. Amazingly, we waited only a short while before a fancy tour bus full of Chinese Businessmen rolled by and we were taken on board, for a fee. The fee was not monetary, they made us sing songs on a microphone in the bus. They got a real kick out of the whole thing. Luckily Alice and Martin know good European songs. They brought us right into Lhasa and presented those that sang with khatas.

All in all the trip was an amazing success, but we were all too tired to think about it much.