I found this description on a website describing another Chinese city, but it applies perfectly to driving in Lhasa, or anywhere else in China for that matter:

The rule of the road is "me first," regardless of signs, traffic lights, road markings, safety considerations, or common sense, unless someone with an ability to fine or demand a bribe is watching. In general, the bigger your vehicle, the more authority you have. Maximum selfishness in the face of common sense characterizes driving in general, and there is no maneuver so ludicrous, unreasonable, or unexpected that someone will not attempt it. Residents have time to adapt -- visitors do not. Our strong advice is to forget it, and take a taxi.

This is also my advice, but there's little to worry about since foreigners can't have cars or motorbikes. Instead, what should be done is cultivation of the "close the eyes and pray your driver is not still drunk" method. On my first ride into town from the train station, our driver turned onto one of those four lane highways with the cement and pretty plant dividers between the opposing two lanes of traffic. This is not strange at all, usually, one crosses the intersection to the other side of the road and turns left into the proper lane. However, our driver saw that it would be far faster to turn directly left into two lanes of oncoming traffic, then "sneak" back across the divider into his proper lane only when a larger vehicle was coming straight at us, provided of course it waited until there was an opening in the cement divider. I thought he was just crazy, but this is actually a normal policy for drivers in China. I have actually witnessed a Chinese driver in a fancy new SUV purposely bump a police man, who was on foot, until he moved out of the way and unhooked a rope that was blocking traffic due to construction on the street. Our driver had the same kind of SUV, but he is Tibetan, so we drove the fifteen minutes around the construction. I didn't catch the red character on the Chinese man's license plate, but the police didn't seem to want to do much about being pushed around so I would guess that the driver had some kind of special hat on or something.

The other day, I saw a taxi driver wait until the light was red, and then proceed into the busy intersection just to the right of the Potala. All this crazy driving wouldn't be quite so bad if the pedestrians and bicyclists weren't operating under what appears to be the same insanity principle.

In any case, here are some more pictures of trips around Lhasa. Our valiant leader, Lhakpa, took us to see the Potala on a Friday, but there are few pictures because none are allowed to be taken inside.

The foreign students entering the museum of the "Old Palace". Here Lhakpa begins his descriptions and dissertations on the sights and sounds of Lhasa's most famous landmark.

The steep steps up to the palace itself are quite a hike, bring extra lungs if possible. Some tourists try to visit on their first day in Lhasa, apparently also operating under some sort of similar insanity principle to the one formulated here: All foreign tourists act in accordance with the belief that "they know better". I, of course, am no longer a tourist, as I have my resident permit, so I operate under a different insanity principle, namely that even if I have no idea what I am doing, I'm going to do it anyway.

The steep steps up to the palace itself are quite a hike, bring extra lungs if possible. Some tourists try to visit on their first day in Lhasa, apparently also operating under some sort of similar insanity principle to the one formulated here: All foreign tourists act in accordance with the belief that "they know better". I, of course, am no longer a tourist, as I have my resident permit, so I operate under a different insanity principle, namely that even if I have no idea what I am doing, I'm going to do it anyway. A young man helps his elder up the steps for pilgrimage, passing the slow moving foreigners as they go up up up...

A young man helps his elder up the steps for pilgrimage, passing the slow moving foreigners as they go up up up... and up up up up...

and up up up up... The view from high on the stairs. I have no sarcastic comment ready for this grand square of the people of the PRC...

The view from high on the stairs. I have no sarcastic comment ready for this grand square of the people of the PRC... The workers on the roofs of the buildings in front of the Potala. They used to house various people that worked in the red or white part of the Palace.

The workers on the roofs of the buildings in front of the Potala. They used to house various people that worked in the red or white part of the Palace.

More stairs...

More stairs... Nearing the main buildings...

Nearing the main buildings... Lhakpa in action.

Lhakpa in action. The great entryway. I asked Lhakpa many questions but what I should have asked was why Tibetans insist on making extremely steep steps. My theory is that, a long time ago, they just started building doorways and had to figure out steps later on...but by the time they did it was already fashionable to have ridiculously dangerously steep steps at the entrances of monasteries and all important buildings, so they never really tried to build properly fitting steps. The insanity principle at work in Tibetan architecture: if it is not really high and really hard to get to, then it's not important enough to warrant really ridiculously dangerously steep steps.

The great entryway. I asked Lhakpa many questions but what I should have asked was why Tibetans insist on making extremely steep steps. My theory is that, a long time ago, they just started building doorways and had to figure out steps later on...but by the time they did it was already fashionable to have ridiculously dangerously steep steps at the entrances of monasteries and all important buildings, so they never really tried to build properly fitting steps. The insanity principle at work in Tibetan architecture: if it is not really high and really hard to get to, then it's not important enough to warrant really ridiculously dangerously steep steps.

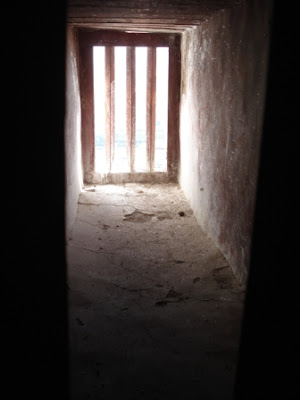

The walls are several meters thick in places:

This thickness made window building particularly unpopular with carpenters of the 15th century and lead to an overall trend of less windows, better building.

This thickness made window building particularly unpopular with carpenters of the 15th century and lead to an overall trend of less windows, better building.Seriously though, the tops of walls in the Potala exhibit one of the unique facets of Tibetan architecture, the Benma wall, which are made of, you guessed it, Benma grass. The grass is bundled very tightly after being dried and then cut to length for building the tops of houses and monasteries, apparently because they never heard the story of the three little pigs. No, actually, it is used to build instead of stone so that they can build higher without the weight of the roof causing architectural disaster. The Benma grass is painted in a sort of burnt reddish color so as to provide "a decorative role by offering a strong color contrast with the dominant white, resulting in a good visual aesthetic feeling." One should note that the Benma walls reflect the strict class system that prevailed in Tibet, prior to liberation. Of course, the great magazine article writer Cedog, whom we have to thank for his insight into Benma architecture, is of the opinion that the architecture originated with the common people, but developed into a class defining symbol only later in history.

Can you see the Benma at the top there? Not very well I'm afraid. In anycase, the look is quite distinctive because the white stone is smooth and the red Benma has a strange sort of "pile of sticks" look. The man standing by the window is refreshing the white on the walls. Interestingly, the white is not paint, but a mixture of water and some sort of white barley, which makes it edible. Really, I saw a dog licking it on the way up the steps. No, just kidding....

Can you see the Benma at the top there? Not very well I'm afraid. In anycase, the look is quite distinctive because the white stone is smooth and the red Benma has a strange sort of "pile of sticks" look. The man standing by the window is refreshing the white on the walls. Interestingly, the white is not paint, but a mixture of water and some sort of white barley, which makes it edible. Really, I saw a dog licking it on the way up the steps. No, just kidding.......Really, it's quite good actually. I tasted some, just like tsampa...

no, not really. I heard someone got sick recently from eating it.

No, just kidding, it really is edible. I had it with rice crispies once.

Lhakpa said it was edible...

mmmmm tasty. See, that guy has a bottle of it right there.

mmmmm tasty. See, that guy has a bottle of it right there. They've applied so much that you can almost ice climb the Potala these days...

They've applied so much that you can almost ice climb the Potala these days...Now, if you would please turn your serious scholarly attention to the murals:

Almost every monastery has the four protectors somewhere near the door. Here are some pictures of the unique masterpieces of Tibetan art at the entrance of the Potala. Note that the Potala is not a monastery per se, but primarily a political building (or set of buildings) that housed both white (Religious) and red (Political) interests.

Almost every monastery has the four protectors somewhere near the door. Here are some pictures of the unique masterpieces of Tibetan art at the entrance of the Potala. Note that the Potala is not a monastery per se, but primarily a political building (or set of buildings) that housed both white (Religious) and red (Political) interests. oooooh, he's much more of a "protector" with his blue sword than the bug-eyed guy with the jewel spitting mongoose:

oooooh, he's much more of a "protector" with his blue sword than the bug-eyed guy with the jewel spitting mongoose: Sorry, the flash got in the way of the jewel spitting mongoose's face.

Sorry, the flash got in the way of the jewel spitting mongoose's face. This guy was laying down on the job.

This guy was laying down on the job. Sorry folks, no pictures from inside, but here's the back side.

Sorry folks, no pictures from inside, but here's the back side. There were quite a few pilgrims circumambulating the Potala and we met some as we came out the back of the palace and headed for the famous LuKhang, or Naga Temple.

There were quite a few pilgrims circumambulating the Potala and we met some as we came out the back of the palace and headed for the famous LuKhang, or Naga Temple. It's a mother and daughter reunion...It's only a motion away? I could never figure out the lyrics to that song.

It's a mother and daughter reunion...It's only a motion away? I could never figure out the lyrics to that song. There were even littler ones on pilgrimage too

There were even littler ones on pilgrimage too "I can almost reach it...almost"

"I can almost reach it...almost" What we all came to see in the park behind the Potala, monkey bars and swings...

What we all came to see in the park behind the Potala, monkey bars and swings... There's the LuKhang in the lake, where the Nagas come from.

There's the LuKhang in the lake, where the Nagas come from. The bridge to the LuKhang.

The bridge to the LuKhang. Sunlight and sang at the LuKhang.

Sunlight and sang at the LuKhang. It was substantially warmer that day than it is now in December.

It was substantially warmer that day than it is now in December.More on insane people and other sights around Lhasa soon...